Target

Halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five within a decade (by 2018)

Key points

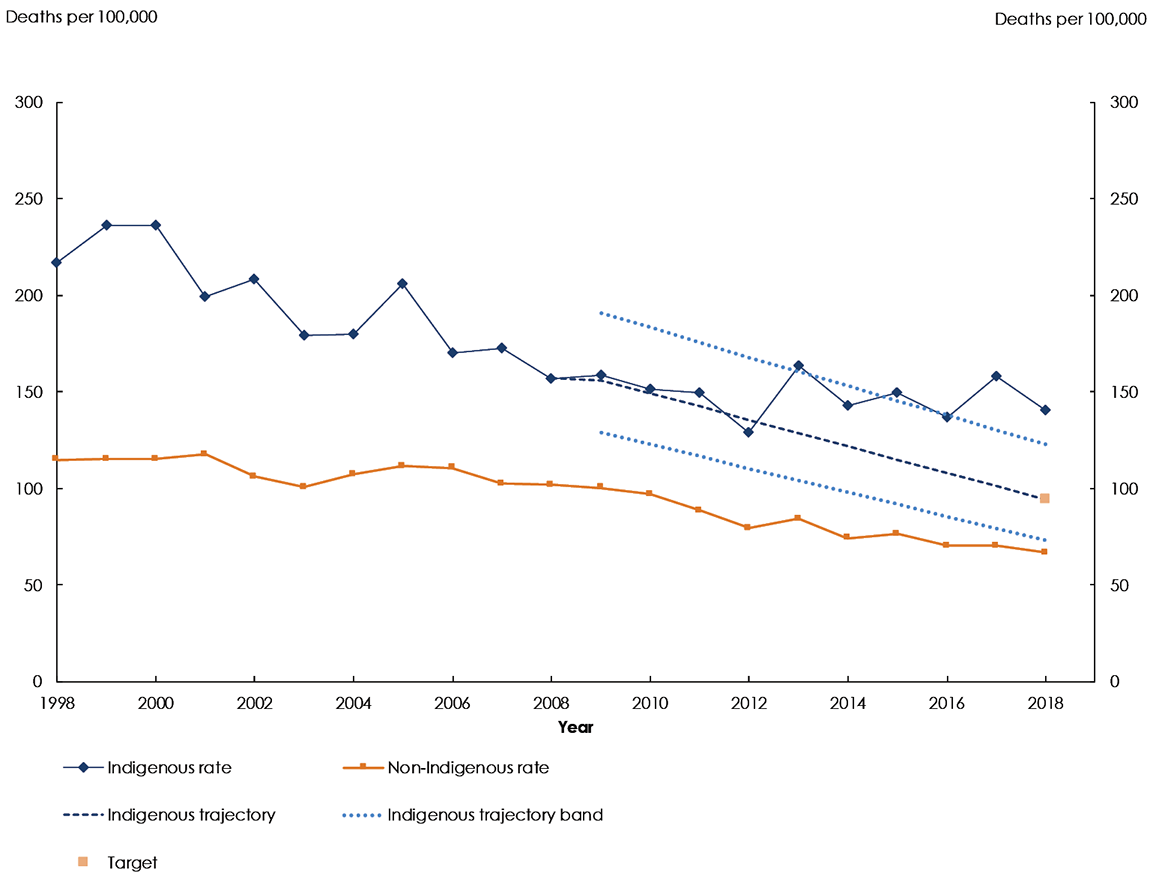

- In 2018, the Indigenous child mortality rate was 141 per 100,000—twice the rate for non-Indigenous children (67 per 100,000).

- Since the 2008 target baseline, the Indigenous child mortality rate has improved slightly, by around 7 per cent. However, the mortality rate for non‑Indigenous children has improved at a faster rate and, as a result, the gap has widened.

- Some of the major health risk factors for Indigenous child mortality are improving. There is a need for further research to understand why these improvements have not translated into stronger improvements in Indigenous child mortality rates.

What the data tells us

National

Tragically, in 2018, there were 117 Indigenous child deaths. This was equivalent to a rate1 of 141 per 100,000—twice the rate for non-Indigenous children (67 per 100,000). This was not within the range required to meet the target (94 per 100,000) (Figure 1.1).

Maternal health is a key driver for this target, and health outcomes for Indigenous mothers and children have improved over the past decade. However, this has not translated into stronger improvements for Indigenous child mortality rates. Further research (including data linkage) is required to understand why. This is discussed in more detail below at Factors that influence Indigenous child mortality.

Indigenous child mortality rates have improved (by 7 per cent) between 2008 and 2018.2 However, this improvement was not as strong as prior to the 2008 baseline.3 Non‑Indigenous child mortality rates also improved between 2008 and 2018, and at a faster rate than for Indigenous children. Therefore, the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous child mortality rates has widened.

Over the period 2014 to 2018, the main cause of Indigenous child deaths was perinatal conditions (49 per cent), such as complications of pregnancy and birth. Most Indigenous child deaths (85 per cent) occurred during the first year of life. This was similar for non‑Indigenous children. This is discussed in more detail below at Causes of death.

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare analysis of the National Mortality Database, unpublished, and National Indigenous Reform Agreement Performance Information Management Group, unpublished.

Notes:

- Child mortality rates are based on data for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory combined.

- The Indigenous trajectory indicates the level of change required to meet the target. The trajectory has been revised to include the 2016 Census-based backcast population estimates. Consequently, the target has also been revised to reflect the result needed to halve the gap (as measured at the 2008 baseline).

- The low Indigenous child mortality rate in 2012 is likely to reflect the unusually large number of Indigenous infant deaths that occurred in 2012, but were registered in 2013. This also results in an overstating of mortality rates in 2013. In 2015, Queensland included Indigenous status from the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death which led to an increase in the number of deaths identified as Indigenous. Although this was an improvement in data quality, it contributed to data volatility and thus caution is required in interpreting annual variation. See the Technical Appendix for further information.

View the text alternative for Figure 1.1.

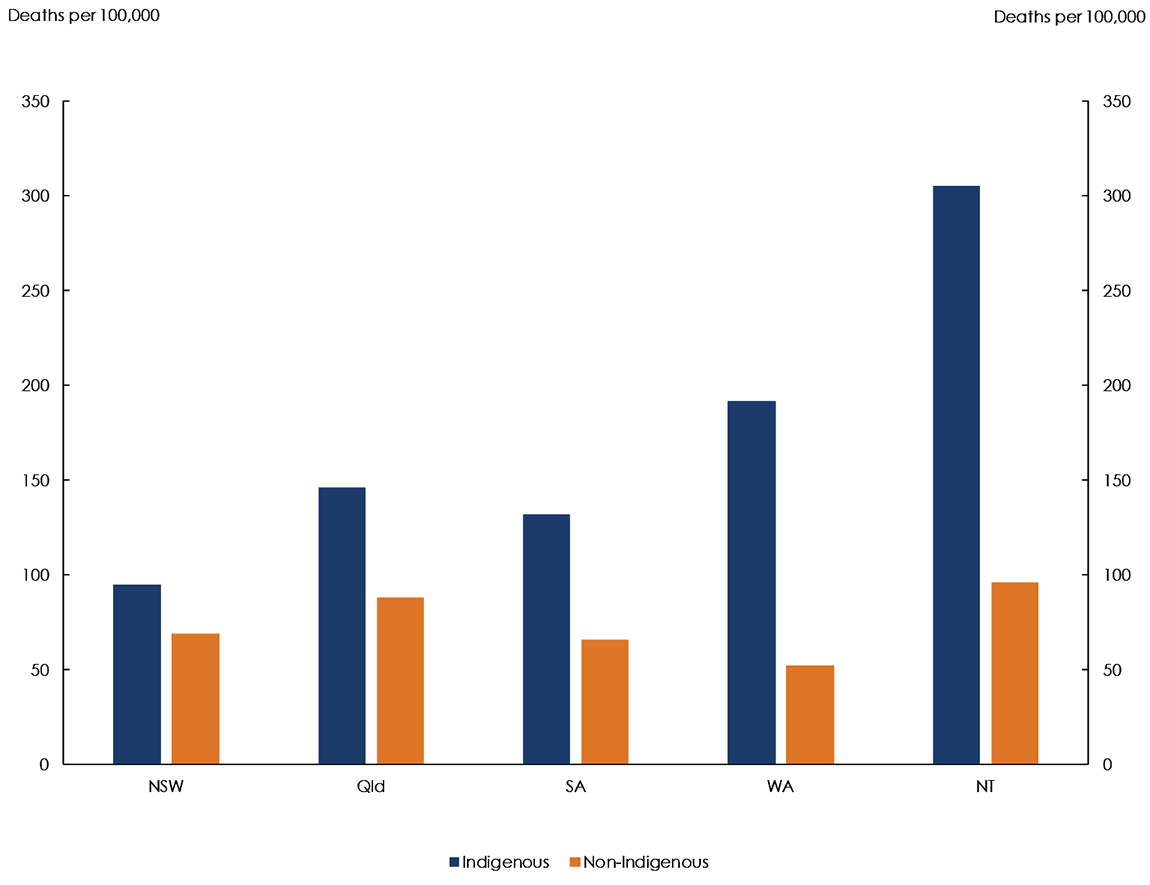

States and territories

Of the five jurisdictions with Indigenous mortality data of acceptable quality, the Northern Territory continued to have the highest Indigenous child mortality rate (305 per 100,000) over the period 2014 to 2018.4 The gap was also largest in the Northern Territory (209 per 100,000) (Figure 1.2). New South Wales had the lowest Indigenous child mortality rate with 95 per 100,000.

Source: Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision 2019, National Agreement Performance Information 2018–19, Productivity Commission: Canberra.

View the text alternative for Figure 1.2.

Causes of death

Over the period 2014 to 2018,5 the main cause of Indigenous child deaths was perinatal conditions (49 per cent).6 For example, birth trauma, foetal growth disorders, complications of pregnancy, respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. This was followed by signs, symptoms and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not classified elsewhere (13 per cent). This includes sudden unexpected deaths in infancy and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

In this period, 514 of the 603 Indigenous child deaths (85 per cent) were infants (less than 1 year old). More than half (57 per cent) of these infant deaths were due to perinatal conditions. About 15 per cent of Indigenous child deaths were children aged 1–4 years old, nearly half of which were from external causes (including transport accidents, drowning, other accidents and injuries).

In 2018, the Indigenous infant mortality rate was 1.8 times as high as for non-Indigenous infants (5.1 compared with 2.9 per 1,000 live births). The trend in infant mortality is similar to child mortality. The Indigenous infant mortality rate has improved slightly between 2008 and 2018, but not as strongly as prior to the 2008 baseline.7 Non-Indigenous infant mortality rates have improved at a faster rate since 2008, so the gap has not narrowed.

Factors that influence Indigenous child mortality

Child mortality is associated with a variety of health and social determinants. Although a complex set of factors are involved, maternal health (such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes) and risk factors during pregnancy (such as smoking and alcohol use) are key drivers of birth outcomes and deaths among Indigenous children. However, access to quality medical care, public health initiatives and safe living conditions serve as protective factors and can improve the chances of having a healthy baby (AIHW 2018).

The prevalence of some of these factors is broadly improving. There has been an increase in Indigenous mothers attending antenatal care in the first trimester, a slight increase in attendance at five or more antenatal sessions, and a decrease in smoking during pregnancy (AIHW 2019).

However, progress in these indicators has not translated into a stronger improvement in Indigenous child mortality rates. Substantial gaps still exist between outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous mothers and babies. There is a need for more progress in this area and further research (including data linkage) to better understand the reasons why.

Data notes

Progress against this target is measured using the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) mortality data for 0–4 year olds.

ABS Indigenous deaths data are reported for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory only, which are considered to have adequate levels of Indigenous identification suitable to publish.

The Indigenous child mortality rate is influenced by changes in Indigenous identification in the deaths data as well as in data sources used in calculating population estimates.

The number of Indigenous child deaths is volatile from year to year. This can reflect real variations in the numbers of deaths, lags in the registration of births and deaths, and changes in Indigenous identification.

The denominator for these statistics has been rebased using the July 2019 release of Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, ABS, 2006 to 2031. Consequently, previously published mortality rates are not comparable to those published in this report.

For more information see the Technical Appendix.

[1] The child mortality rate is defined as the number of deaths among children aged 0–4 years old as a proportion of the total number of children in that age group, presented as a rate per 100,000 population. Note that the number of Indigenous child deaths is volatile from year to year.

[2] This result was not statistically significant. References to per cent change in mortality rates in this chapter are derived through linear regression analysis, and tested at the 5 per cent level of significance. For details on the specifications for the child mortality indicator used in this report, refer to the National Indigenous Reform Agreement data specifications on the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) METeOR website.

[3] Data quality issues may overstate the early declines from 1998 to 2008. See the Data notes and the Technical Appendix for further information.

[4] Five years of data are combined for more detailed reporting of Indigenous child and infant mortality by state and territory to overcome the volatility in rates associated with the small numbers involved.

[5] Five years of data are combined for more detailed reporting of Indigenous child mortality by cause to overcome the volatility in rates associated with the small numbers involved.

[6] Perinatal conditions originate during pregnancy (from 20 weeks of gestation) and up to 28 days after birth.

[7] The improvement in the Indigenous infant mortality rate from 2008 and 2018 was not statistically significant.